Lessons: 9 - 12

This is the second part in my ‘Lessons’ series. I’ve learnt many lessons (some I wish I didn’t learn) through many mistakes, and wanted to share these light-hearted, tongue-in-cheek short stories. They are usually attached to fond memories.

#9. The Conditions

What are the conditions? Is it greasy? Is it dry?!

'Good' climbing conditions in the U.K. are usually fickle and hard to predict. To climb on dry, warm rock with ample friction, whenever you like, is actually quite rare.

Our varied weather (read ‘terrible’) makes things difficult, as does the location of our crags. They’re often submerged by the sea half the time (tidal), covered in birds (restricted access) or in the mountains (bad weather). Even ‘God’s Own Rock’ (the grit) is rarely climbed on outside of autumn/winter. If you want to start a heated debate, just talk to the average British climber about conditions.

This is without talking about winter climbing - an even more niche aspect of our sport. I thought conditions were relatively simple until I tried to explain to my guest, Ian Welsted, about ethics and conditions during the BMC International Winter Meet. ‘We can’t go there, because it’s not white…’

If you manage to find good conditions, you’d better make the most of it. They’re given affectionate names, such as ‘bon cons’ and ‘decent connies.’ You can even rank your conditions on a scale: Bon Con 1 is primo, and Bon Con 5 is raining!

Here’s some of my lessons learnt from trying to climb routes ‘in condition.’

Sea Cliffs. e.g. Gogarth

Perhaps the hardest to find ‘in condition,’ because of the sea and dreaded ‘grease.’

Sunshine is the first ingredient. You must have sunshine, because it burns off the grease which covers the rock. Gogarth’s Main Cliff only gets the sunshine from about 1pm, so enjoy a lie in.

Wind is the second ingredient. A gentle breeze helps to clean the crags (honest), and moves the air around. It also reduces humidity. 15/20 mph is too much wind if it’s a south-westerly, because it might cause the fourth ingredient. 10 mph SW is good for Gogarth; in summer it can be unbearably hot, but not if there’s a good breeze.

Low tides are the third ingredient. This is mainly due to access (in the example of Gogarth), but is so important it counts as ‘conditions.’ Think of Pembroke: one of the best climbing areas in the UK - but only if you’ve got the right end of a tide timetable. Low tides also help to keep the moisture away from the cliff face.

Calm seas are the fourth ingredient. If there are lots of waves crashing into the crag, the spray from the sea will hit the cliff, and increase humidity/moisture in the air. I’ve been unable to access routes at Gogarth because of rough seas, as well as greasy.

In summary: sunshine, a gentle breeze and low tides are usually good conditions for sea cliff routes.

Mountain Crags e.g. Cloggy.

(I’m biased towards North Wales, obviously).

The main ingredient for these crags is a period of dry, sunny weather. These crags often have lots of vegetation on them/above them, and therefore seep for a long time.

Because they’re in a mountain environment, they also get rained on a lot. A week of dry weather (sometimes just a few days) is good for Cloggy. It’s also north-facing, so will be chilly outside of summer.

Settled ‘high pressure’ weather is also useful. This means the winds should be light and the cloud cover minimal. A few days of stable weather usually appear in May and August for Cloggy, and then it’s time to head to the mountain crags.

In summary: when it’s too hot to go to Gogarth (July/August) and there’s been a settled, dry spell of weather, get yourself to Cloggy!

Grit

I include this simply because it highlights my glaring lack of gritstone climbing. Everyone knows you need good friction for the grit, so autumn/winter/spring are the prime times to climb. Someone said the optimum temperature is 5 degrees C, which sounds fresh! Ask the gritstone wads for the knowledge. I suspect sunshine and crisp, clear skies are the answer.

#10. Talking the Talk

The language of British climbing, much like the conditions, is a rich and varied subject. It’s as much a part of climbing as climbing itself, and to overhear some climbers in the pub is like hearing a secret code being discussed. ‘Take the gaston, rock over to a crimp and then pinch the arete.’

Of course, phrases come in and out of vogue. There’s a certain brilliance to some sayings, such as ‘doing a Ricky’ - apparently this means to be on redpoint on a sport route. Redpoint…Ricky Redpoint (alliteration)… Ricky!

These are some of my favourite phrases:

‘Smash like instant mash potato’

I think this came form Rhys Harries.

‘Come on arms, do your stuff!’

The Ron Fawcett Lord of the Flies classic.

“I said ‘come on arms, but they told me to fuck off!’ I fell for miles!”

Unknown.

‘Chossmonger/cheesemonger’

A great way to describe someone psyched for loose and dangerous routes.

‘Cheese and biscuits’

An appropriate thing to say whilst being a chossmonger.

‘Chossbashing’

When you enjoying some quality cheese and biscuits.

‘Chopstick’

Alex Hallam’s amazing adaptation of being a ‘chopper/punter.’

‘Getting ‘er done’

A Canadian way of saying ‘sending the route.’

‘In the saddle!’

An American way of saying ‘getting ‘er done.’

There’s plenty of ways to say you’re keen:

‘Amped, stoked, psyched, revvved, shacked, buzzing, whacked’

Of course, there’s also some great ways to say you didn’t do something, or fell off:

‘Biffed, bonked, chopped, chummed, punted, lobbed, bailed’

‘Terminal pump’

A type of pump you can never recover from, regardless of how big the jug is!

And my current favourite:

‘Enough of the bullshit, it’s time to rage.’

The Torch & The Brotherhood’ article, Kyle Dempster, Alpinist 42.

#11. Being a Dirtbag

A road trip is an integral part of being a climber, and usually involves camping somewhere quiet, or sleeping in a van whilst climbing for weeks on end. In this piece by James Taylor, he describes his ‘van life.’ It accurately sums up living out of your van, and has some useful advice. James recently worked out he’d only slept in a bed about 2 weeks from the past year!

#12. Fixing a blocked Jetboil burner

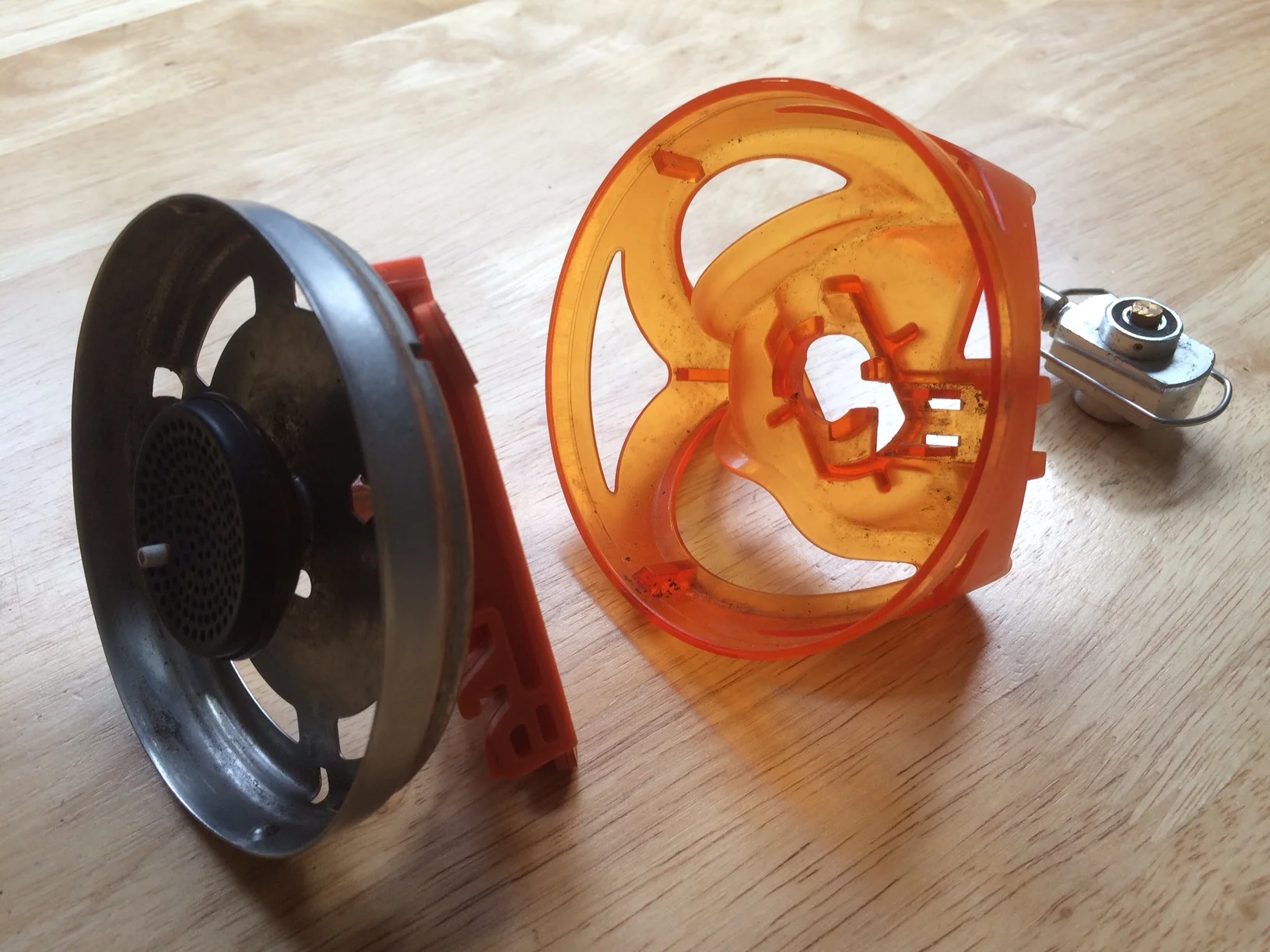

After about 2 years of use, my Jetboil stove stopped burning with its usual roaring flame, until it eventually only produced a very faint flame. There was obviously a blockage somewhere in the burner.

I first tried soaking the burner in petrol (obviously making sure the stove was cold!) for 24 hours. Petrol can be a good cleaning fluid. Initially, this improved the flame but the problem soon returned.

With my Dad’s advice, I then dismantled the stove and burner (see photos) and, with a fine needle, removed approximately 2 cm of ‘fluff’ from inside the burner pipe. This immediately cleared the problem and the stove flame has returned to normal levels.

I don’t know how the fluff collected there, or how to prevent it happening again, but I’m pleased it’s fixed. If you’re having trouble with your Jetboil stove, consider this to unblock the burner.

Note: The Jetboil website has some useful advice on how to dismantle the burner. Do all of this at your own risk and be careful. I’m just illustrating how I fixed a problem with my burner, and you should consult Jetboil if you’re not sure.